I’ve always been a fan of Salinger, especially the Glass family stories, though recently I’ve found I am no longer quite as enchanted as I once was. What impressed me about the Glass family as a young adult reader now seems in middle age excruciatingly self-congratulatory. That being said, I still appreciate the narrator’s overwhelming prescence in some of the stories and the almost constant parenthetical digressions in most. I’ve always felt that Salinger shared a bit of Nabokov’s cleverness, and for years I harbored, in one of my more protracted bouts of magical thinking, the ridiculous fantasy that Salinger, like John Ray, Jr. and Vivian Darkbloom, was but another sly fabrication of Nabokov’s.

Conversely, several years ago, a rather hilarious article appeared in the Village Voice entitled Humbert: An Introduction with the subtitle Jerome David Salinger, Author of Lolita. It begins with this preface:

“Editor’s note: In July of this year, cleaning out my “N” file, I discovered the pristine galleys for Mercy Pang’s foreword to a book on Nabokov—one, to my knowledge, never published. Pang was a friend, later enemy, of the family; her current whereabouts are unknown. In truth she drove me up the wall. The title above, after Borges, is my own. I do not know “Chad Ravioli.” —E.P.”

This unpublished book, authored by one “Leif D. Warden” of Ursinus College reveals that Salinger was Lolita‘s ghostwiter and that Salinger’s short story A Perfect Day For Bananafish is its companion piece :

“Citing a cache of letters belonging to his niece, Esmé Rockhead, Warden claims that Nabokov—though indubitably the author of such works as The Eye—did not, in fact, write Lolita. Warden sets about to prove that the author was none other than one J.D. Salinger.”

The article is worth reading for those who may be easily amused. Far more satisfying, is the letter to the editor that appeared the following week, from Richard G. DiFeliciantonio of Ursinus College:

On behalf of the faculty and staff at Ursinus College I’d like to express my pleasure with Ed Park’s bang-up research for his work “H.H.: An Introduction,” [Voice Literary Supplement, November 9–15]. Leif D. Warden was a phony and a snob, and Park is absolutely correct that he never taught in any conventional classroom, choosing instead, smelling of Yuengling, to loiter among the coeds at Wazzner Student Center. However, I want to point out that it was actually Warden’s wife with whom Salinger was allegedly intimate, not his niece. But that’s not important anymore as all the papers were burned at a homecoming bonfire. What is important is that our gem of a college, named for the great German Latinist and theologian Zacharias Baer, sits in the suburbs of Philadelphia; it never has been nor ever will be an institution in western Pennsylvania.

Richard G. DiFeliciantonio

Collegeville, Pennsylvania

http://www.villagevoice.com/2005-11-01/vls/humbert-an-introduction/1

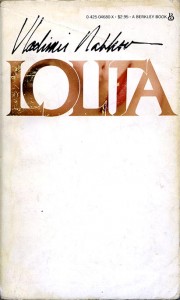

Thanks to Patty for sending this Berkeley Medallion Edition from 1977 that is missing from Dieter Zimmer’s online gallery Covering Lolita. By the way, I have already received several submissions for the Lolita Cover Contest and they are quite interesting! When the contest ends and the winner has been selected I am going to post a gallery of all the entries.

Thanks to Patty for sending this Berkeley Medallion Edition from 1977 that is missing from Dieter Zimmer’s online gallery Covering Lolita. By the way, I have already received several submissions for the Lolita Cover Contest and they are quite interesting! When the contest ends and the winner has been selected I am going to post a gallery of all the entries.