stanislaus polonus, anatol girs, aloys ruppel

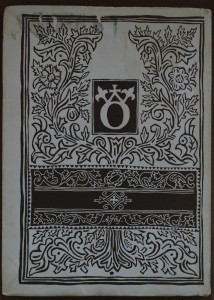

Friday, June 25th, 2010 Alicia Nitecki recently informed me of the existence of a wonderful book designed by Anatol Girs and published by his Oficyna Warzawska im Ausland in 1946, its sixth postwar publication (We Were in Auschwitz, by Tadeusz Borowski, et al, was the third), and dedicated to Boleslaw Barcz (with whom he founded Oficyna Warzawska in 1938 and who was subsequently killed in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944). Entitled Stanislaus Polonus, Ein Polnischer Frühdrucker in Spanien (Stanislaus Polonus, An Early Polish Printer in Spain) this gorgeous book written by German librarian, archivist and historian Aloys Ruppel (1882 – 1977) is an overview of the work of the late fifteenth century printer Stanislaus Polonus who arrived in Seville in 1490 and over the course of fourteen years published 111 titles there. Beautifully printed in an edition of 1600 (of which my copy, purchased from a bookseller in Germany, and not in the best condition is No. 1190) it highlights not only the work of Polonus, but of Girs himself. The letterpress front and back covers printed with brown and orange-red ink on beige paper is absolutely stunning. Inside are lovely examples of Polonus’ work including fantastic woodcuts printed on Japan paper.

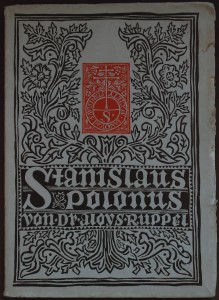

Alicia Nitecki recently informed me of the existence of a wonderful book designed by Anatol Girs and published by his Oficyna Warzawska im Ausland in 1946, its sixth postwar publication (We Were in Auschwitz, by Tadeusz Borowski, et al, was the third), and dedicated to Boleslaw Barcz (with whom he founded Oficyna Warzawska in 1938 and who was subsequently killed in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944). Entitled Stanislaus Polonus, Ein Polnischer Frühdrucker in Spanien (Stanislaus Polonus, An Early Polish Printer in Spain) this gorgeous book written by German librarian, archivist and historian Aloys Ruppel (1882 – 1977) is an overview of the work of the late fifteenth century printer Stanislaus Polonus who arrived in Seville in 1490 and over the course of fourteen years published 111 titles there. Beautifully printed in an edition of 1600 (of which my copy, purchased from a bookseller in Germany, and not in the best condition is No. 1190) it highlights not only the work of Polonus, but of Girs himself. The letterpress front and back covers printed with brown and orange-red ink on beige paper is absolutely stunning. Inside are lovely examples of Polonus’ work including fantastic woodcuts printed on Japan paper.

Interestingly, a much expanded version of this book was published in Krakow in 1970 by Państwowe Wydawn with the Ruppel text translated into Polish by Tadeusz Zapiór.

[To truly appreciate them click on the thumbnails for larger images.]