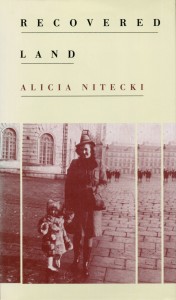

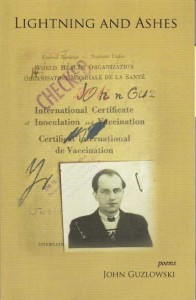

Perhaps central to apprehending the experience of those who endured and bore witness to the myriad horrors of the German occupation of Poland during World War II is acknowledging its persistent influence on those sons, daughters and grandchildren, whose daily lives today, sixty five years on, remain infused with the bitter distillate of loss, trauma, despair and anger, and on whom still rests the burden to comprehend what for most of their lives has been shadowy, elusive, and incomprehensible. John Guzlowski, born in a Displaced Persons camp in 1948 to parents who met in a slave labor camp, has spent his life using his stark and powerful verse to peer through his parents’ eyes, wringing poignant beauty from their terrors. Alicia Nitecki, who was two years old when she and her family were arrested and deported to a labor camp in Lauterbach in 1944, has spent the latter part of her professional life immersed in the literature of the Holocaust, translating the work of Tadeusz Borowski, Mieczyslaw Lurczynski, Henryk Grynberg, and other survivors. As if that weren’t enough, she has given us yet another gift, Recovered Land, a collection of intelligent and discerning essays detailing her return to the places of her early childhood, specifically Warsaw and Lauterbach, but also the slave labor camps of Buchenwald and Flossenburg where her maternal grandfather was imprisoned. These essays articulate beautifully the struggle to come to terms with the past, especially amidst the heavy psychological burdens with which specific places are weighted down. What results is an exploration both fascinating and enriching, and one close to what I feel the Greeks meant by νοσταλγία. With prodigious grace and quiet unassuming wisdom she writes of trying to reconcile her fragmentary memories and the constructed images in her mind with the realities of these places. Of Warsaw she writes, paraphrasing Eliot, “the footfalls that echoed down the passage of my memory led always to a door that opened not into the rose garden but into the city” likening being in Warzaw to “peering at a landscape I knew well late at night when the darkness has hidden all the familiar details.” In Lautenberg she is “searching the pages of a book I’d read looking for a half-remembered passage that would illuminate some half-formulated question.” She is also searching for the father she has not seen since 1946 who is “as shadowy and as solid as the city itself.” Upon their first meeting she expresses her yearning eloquently:

“I wanted only that first immediate recognition and to trace with my finger the familiar geography of my father’s face: the high forehead, the hooded eyes, the hollow of his cheeks; to hug him as I must have hugged him as a child, and in this thoughtless way to confirm the reality of this man to whom I was connected by birth.”

Inevitably, perhaps, and with the sense of sorrow and loss threaded throughout all of the essays, she ends her discussion of her father by saying: “We never did connect, my father and I. The distance between Warsaw and Boston, between the man that he was and the woman I had become, proved in the end too great.”

In the final essay, “Border Country”, Nitecki mentions another loss. Once, upon questioning her mother about a photograph of her grandfather in striped prison garb, her mother snatches it from her and immediately rips it up. Years later her mother offers to let her read her grandfather’s Flossenburg memoir.

“After my mother had died, her dying breath closing the door to my childhood, I searched for the memoir but did not find it, and I regretted our inarticulateness: what my mother, in her desire not to force an obligation on me, had not said, which was that she wanted her father’s memories preserved; what I had never been able to say to her, which was that I was afraid to read them and reluctant to reveal an interest in the horrors he had lived, because such an interest seemed perverse.”

When we spoke recently, Professor Nitecki told me:

“My mother was very fond of my grandfather and was profoundly troubled by his incarceration. She never talked to me about his war experience, she also somehow assumed I knew it, which I didn’t. When I asked her when I was a teenager what he’d done during the war, she responded with rage ‘As you know he was in a concentration camp.’ (which I didn’t know, nor did I really know at the time what those places were like). She ripped the photo up probably because it enraged her to see him like that. I am very sorry that I was never able to locate his memoir. Since I had been born in the middle of the war, she tried when the war was over for me to live a normal, happy life, and, essentially never referred to the past. I decided to visit Flossenburg in order to understand/see what my grandfather had lived through.”

She writes that she “drove there with an uneasy conscience, afraid of appropriating for myself my grandfather’s experience.” Perhaps, as the title Recovered Land seems to suggest, Nitecki finds that she is the sole custodian and bearer of that experience, which is her birthright and her lot. As she notes in “Pictures From Germany”: “those of us who were born in Eastern Europe during the war are exiles from hell, not paradise. War was the first world I knew, and it is as much a part of me as the color of my skin and eyes, my disposition to migraine. I know that winter is the end and the beginning, the chain on which that brilliant gift, spring, is strung as a bead. Perhaps that is why today, chaos, fear, and death are more familiar to me than peace, confidence, and life.”

The deadline for our Book Cover Design Contest No. 4 on Tadeusz Borowski’s This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen is exactly one month away! We have assembled an impressive list of jurors, some of whom will be familiars to frequenters of this site: Alicia Nitecki, John Guzlowski, Jae Rossman, Barbara Girs, and Marco Sonzogni. For a little inspiration here is the working cover design for the forthcoming Yale University Press London translation of Borowski’s stories (translated by Madeline Levine, Professor of Slavic Literatures, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill). It’s worth noting that this translation contains twenty stories in addition to the twelve that comprise This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen (incidentally, the title story is here translated as “Ladies and Gentlemen, Please Come to the Gas.”). I have my doubts that this will be the actual cover, since YUP London used that image on last year’s The Warsaw Ghetto: A Guide to the Perished City by Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak.

The deadline for our Book Cover Design Contest No. 4 on Tadeusz Borowski’s This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen is exactly one month away! We have assembled an impressive list of jurors, some of whom will be familiars to frequenters of this site: Alicia Nitecki, John Guzlowski, Jae Rossman, Barbara Girs, and Marco Sonzogni. For a little inspiration here is the working cover design for the forthcoming Yale University Press London translation of Borowski’s stories (translated by Madeline Levine, Professor of Slavic Literatures, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill). It’s worth noting that this translation contains twenty stories in addition to the twelve that comprise This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen (incidentally, the title story is here translated as “Ladies and Gentlemen, Please Come to the Gas.”). I have my doubts that this will be the actual cover, since YUP London used that image on last year’s The Warsaw Ghetto: A Guide to the Perished City by Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak.  Yale University Press New Haven shows a different and I’d say less interesting cover on their website (left), although something tells me this won’t be the actual cover either.

Yale University Press New Haven shows a different and I’d say less interesting cover on their website (left), although something tells me this won’t be the actual cover either.