“What was done to people locked up behind wires and dressed in stripes simply defies description.” – Mieczysław Lurczyński, Preface, The Old Guard

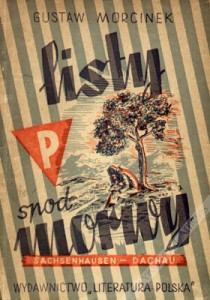

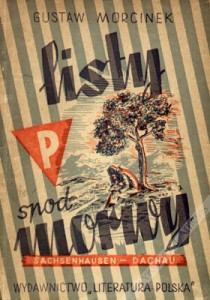

World War II casts a long shadow over history. Remarkably, fifty and sixty years later, there are still works of Holocaust literature being published in English translations for the first time. And, shamefully, there are other books that for one reason or another may never see publication in English. An unfortunate example of the latter is Gustaw Morcinek’s Listy spod morwy (Letters from Under a Mulberry Tree). Morcinek (1891 – 1963) was an important author who had written a dozen books during the interwar period. He was arrested on September 6, 1939, a mere six days into the German invasion of Poland, and spent the entire duration of the war in concentration camps, first in Sachsenhausen and then in Dachau from March 1940 until the camp was liberated in April 1945. Letters from under a Mulberry Tree, a collection of a dozen essays, was written in France that summer. According to Alicia Nitecki, “in its disawoval of any claims to ‘heroism’ or ‘martyrdom’ and its unflinching portrayal of what existence in the camp revealed about human nature (“A psychologist would have wonderful material here to study and deepen his knowledge of man,‘ Morcinek wrote) the work is indeed close in spirit to that of We Were in Auschwitz.” Someday, hopefully soon, we will be able to read it!

World War II casts a long shadow over history. Remarkably, fifty and sixty years later, there are still works of Holocaust literature being published in English translations for the first time. And, shamefully, there are other books that for one reason or another may never see publication in English. An unfortunate example of the latter is Gustaw Morcinek’s Listy spod morwy (Letters from Under a Mulberry Tree). Morcinek (1891 – 1963) was an important author who had written a dozen books during the interwar period. He was arrested on September 6, 1939, a mere six days into the German invasion of Poland, and spent the entire duration of the war in concentration camps, first in Sachsenhausen and then in Dachau from March 1940 until the camp was liberated in April 1945. Letters from under a Mulberry Tree, a collection of a dozen essays, was written in France that summer. According to Alicia Nitecki, “in its disawoval of any claims to ‘heroism’ or ‘martyrdom’ and its unflinching portrayal of what existence in the camp revealed about human nature (“A psychologist would have wonderful material here to study and deepen his knowledge of man,‘ Morcinek wrote) the work is indeed close in spirit to that of We Were in Auschwitz.” Someday, hopefully soon, we will be able to read it!

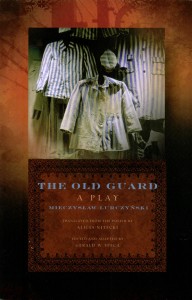

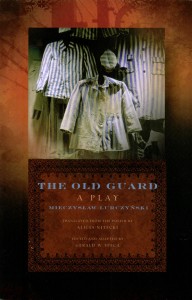

Stara Gwardia (The Old Guard) by Mieczysław Lurczyński (1908 -1992), published this year in a searing translation by Nitecki, is a fortunate example of the former. A member of the Polish Home Army, Lurczyński was arrested in February 1943 and after a month in Pawiak Prison and a week in Majdanek was transported to Buchenwald. In February 1945 he was transferred to SS-Kommando Hecht in Escherhausen. He managed to escape from the train transporting the prisoners out of the camp as it was being evacuated at the end of March 1945. Like Morcinek and Letters from under a Mulberry Tree, no sooner had Lurczyński gained his freedom than he began writing The Old Guard. Nitecki notes in her introduction that “the play is based on situations its author had witnessed, characters he had seen, and conversations which he had noted down verbatim on scraps of paper in Buchenwald and its sub-camp SS-Kommando Hecht, and had miraculously managed to smuggle out of the camps with him.”

In his own preface Lurczyński writes that the “the play does not have any great atrocities in it. The focus, rather is on internal experiences and on depicting pained, sick, desperate , and resigned psyches, on depicting the methods by which people were turned into beasts, and beasts into freaks of nature.” Acutely aware that the language of the play was “the depraved language of a human cesspool” he elected to print only 200 copies and to personally distribute them to people “who will tolerate the raw breath blowing from its pages, and who will realize the moral imperative of telling the truth…at any price.” And indeed the raw callousness with which the characters describe the depravity around them is harrowing, and the venomous rage present in the characters’ exchanges is disagreeable and disarming, suggesting a much more recent play at perhaps a greater remove from its subject matter. It is to Nitecki’s credit that she chose not to tone down the play, but instead unleashed it full force, which no doubt some readers may find offensive.

At the heart of the play (set in the single room where all three acts take place) is the struggle between Geniek, the thuggish, debased, disillusioned Lageraeltester (the Camp Elder, a prisoner in charge of the camp and answerable to the Commandant) and Fryderyk, “an old actor of considerable renown; a man of the 19th century: romantic, self-centered, idealistic…a relative newcomer.” Fryderyk, who as Professor Nitecki tells us in her introduction, is modeled on “Fryderyk Jarosy (1890 – 1960) a theater director, film actor, and reknowned king of Warsaw cabaret.” is a sort of elder statesman, a civilized relic from a saner era who because of his relatively privileged status within the camp has so far has managed to resist its dehumanization. As he says in one scene:

“I was part of the scene where Wedekind performed on the guitar, where one evening Chaliapin at the dawn of his fame sang Russian folks in a bass voice, where the divine Eleanor Duse and Sarah Bernhardt and the satirist Heine passed through, where Thoma and Rilke, still young and unknown, came by. I had the good fortune to see the beginnings of contemporary French art and music. Next to me, Picasso created the first of his works, Debussy played. I took part in creating theatre with Rheinhardt who was financed by my father among others. I had the fortune to spend time in Austria where the exiled Meyrink wrote his political satires. As a young diplomat, I managed to get to know the court of Nicholas II, Francis Jozef, and Wilhelm II; I witnessed the behind-the-scenes negotiations and trivialities. I studied in England at Oxford…”

In fact, Lurczyński noted later that “a conversation with him was an escape, it allowed me to get a breather from the primitiveness and bestiality surrounding me on all sides.”

In contrast, witness Geniek’s stunning ἀπολογία directed at Fryderyk, arguably the play’s most powerful passage:

“We, the old guard, the old numbers…do you know what number I have from Auschwitz?

(shows his tattoo)

See. 7000. 1940. We the Alte Garde, we’ve survived everything and we’ll survive this, too, because we are the future of Poland, the backbone on which everything will depend. You weren’t in Auschwitz; you didn’t see what we saw. For us, dying was like shitting is to everyone else. You don’t know a goddamned thing, that’s the problem. Did an SS man choke you half to death like Palitsch did me? Did you squeeze into a bunker, crammed with twelve others – in 9 square feet of space! – when the little high window got frozen over from our breathing and you couldn’t reach to wipe it clear? I was taken out for interrogation and the others croaked, suffocated over the next few days, the window frozen over. They were carried out before my eyes. Six days without eating and to die from a lack of air! Have you experienced anything like that? So how can you know? Did you see how the Russkies gave a beating? How they’d pick a guy up and slam him to the ground so that they’d rupture his kidneys. And he’d swell up and lie dying for weeks on end. Or how they’d hold a victim under water in such a way that he wouldn’t drown. By the hour, in the Block gutters where the fucking Holzschuhe are washed. I saw a Kapo from Cologne, a German Gypsy, built like that –

(demonstrates the wide breadth of the man’s shoulders)

who was beaten in Buchenwald for half a day and then was carried out in a wheelbarrow, a pile of meat vomiting blood, and dumped behind the small Lager. And then I saw that pile of meat leap up and run, blindly, with dislocated shoulders, to the gate, seeking safety with the SS.

(he drinks)

So what do you know, you old rat fuck? Huh? What the fuck do you know? You didn’t get to experience the Lager thanks to my good graces. Did you see the first mass extermination at Auschwitz? Were you there? In the evening, six hundred people were called out and herded into Block Eleven. Nobody believed – nobody wanted to believe – they would be shot. But already, in the morning wagons were pulled through the Lager loaded to the top with corpses still leaking blood like pigs. I myself pulled a wagon…and behind us we left a broad trail, like a bubbling red stream. The wind blew back the canvas and we saw the naked bodies, riddled with bullets, with bared teeth and eyes wide open. For weeks I loaded corpses, was a Leichentraeger. Two of us would pick up a body by its extremities and swing it – hup, hup, hup – into the air and onto the wagon where it would land among its shit-caked and foul-smelling kinsmen. My first three days on the job, I couldn’t eat a thing. And I was hungry, friend. I’d’ve settled for anything: a crust of stale bread or some soup made from rutabaga and old gramophone records. But I couldn’t eat. My hands were thick with fat from the corpses and there was nowhere I could wash them.

(pause)

That’s what times were like. And now you want me to regret the loss of a bowl? I’ve got bowls up the ass in the Block. Let those cocksuckers organize for what they need wherever they can, the way I organized old food cans from the garbage so that I could find enough peelings to make a half cup of soup. Fucking money-grubbing, ass-fucking millionaires! What do I give a shit about them? Did you see my number? The first transport to Auschwitz, two years of penal Kommando in Birkenau, where organizing the dregs from SS lunches was hog heaven. I shit blood for two weeks after getting typhus – do you hear me? Typhus! – wasn’t able to eat a thing. People like me will be the future of Poland. We know what we have to do. Our Lager education will come in handy.”

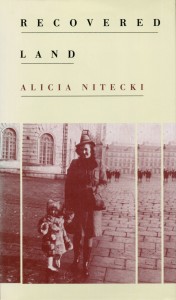

Very special thanks to Alicia Nitecki for her introduction to and translation of The Old Guard, Excelsior Editions, SUNY Press, 2010. Information from Letters from under a Mulberry Tree is from Beyond the Archives: Research as a Lived Process.

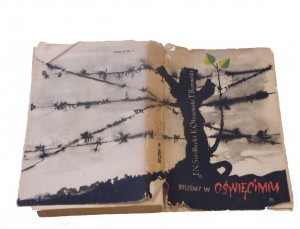

The deadline for our Book Cover Design Contest No. 4 on Tadeusz Borowski’s This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen is exactly one month away! We have assembled an impressive list of jurors, some of whom will be familiars to frequenters of this site: Alicia Nitecki, John Guzlowski, Jae Rossman, Barbara Girs, and Marco Sonzogni. For a little inspiration here is the working cover design for the forthcoming Yale University Press London translation of Borowski’s stories (translated by Madeline Levine, Professor of Slavic Literatures, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill). It’s worth noting that this translation contains twenty stories in addition to the twelve that comprise This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen (incidentally, the title story is here translated as “Ladies and Gentlemen, Please Come to the Gas.”). I have my doubts that this will be the actual cover, since YUP London used that image on last year’s The Warsaw Ghetto: A Guide to the Perished City by Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak.

The deadline for our Book Cover Design Contest No. 4 on Tadeusz Borowski’s This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen is exactly one month away! We have assembled an impressive list of jurors, some of whom will be familiars to frequenters of this site: Alicia Nitecki, John Guzlowski, Jae Rossman, Barbara Girs, and Marco Sonzogni. For a little inspiration here is the working cover design for the forthcoming Yale University Press London translation of Borowski’s stories (translated by Madeline Levine, Professor of Slavic Literatures, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill). It’s worth noting that this translation contains twenty stories in addition to the twelve that comprise This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen (incidentally, the title story is here translated as “Ladies and Gentlemen, Please Come to the Gas.”). I have my doubts that this will be the actual cover, since YUP London used that image on last year’s The Warsaw Ghetto: A Guide to the Perished City by Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak.  Yale University Press New Haven shows a different and I’d say less interesting cover on their website (left), although something tells me this won’t be the actual cover either.

Yale University Press New Haven shows a different and I’d say less interesting cover on their website (left), although something tells me this won’t be the actual cover either.