the secret sonnets, joseph mellen (glucocracy, 1976)

June 5th, 2015

you are my queen and at our coronation

a hallelujah chorus I will sing

and celebrate with hymns of trepanation

the fact that you are queen and I am king

– the secret sonnets, xxiv

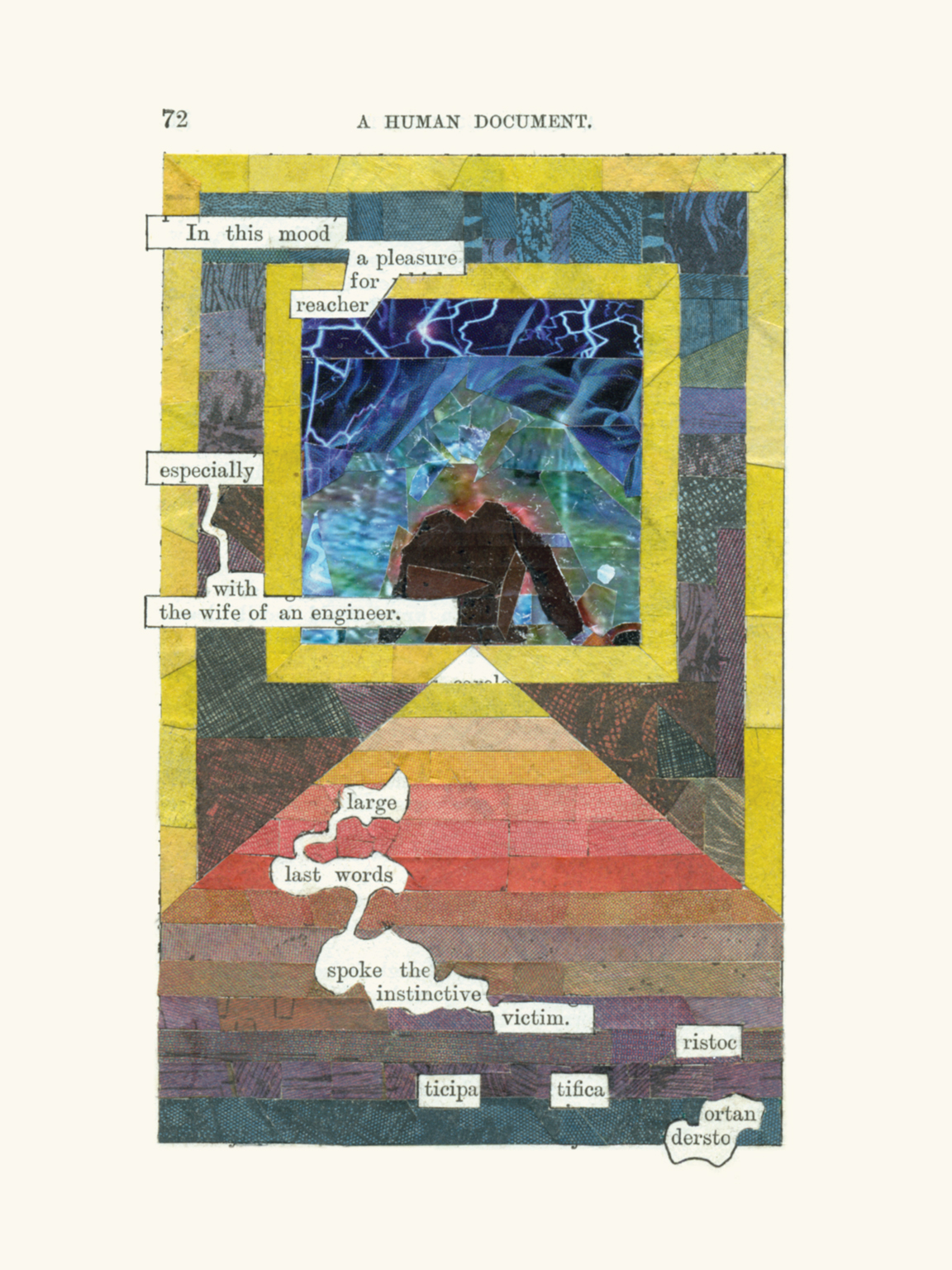

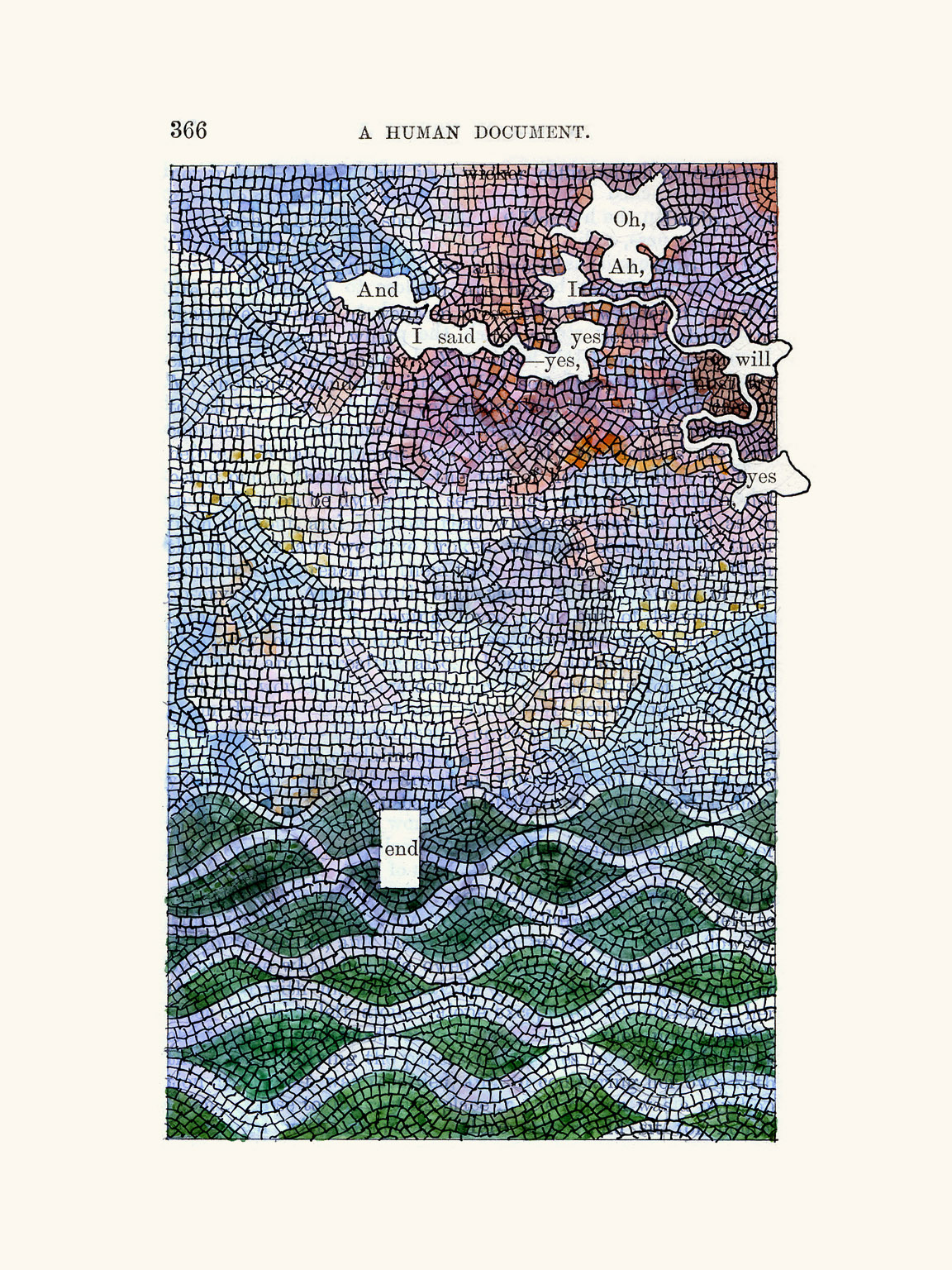

We live in a quotidian age. Those experiences when the thread deliriously unwinds from its bobbin, (those descents into chaos of the good and exciting kind as opposed to the screaming in fear and pain variety) have become increasingly rare delectations. Every so often, however, a thread is pulled and in unexpected fashion the metaphorical sweater thrillingly unravels and the world once more is shot through with magic and possibility. Recently, one such experience happened to me. While perusing the shelves in a thrift store I found a small hardbound book that bore the hallmarks of being self-published (somewhat crudely bound, no ISBN), and I bought it, simply because embossed in silver on its navy blue faux pigskin bindings were three words: THE SECRET SONNETS. I thought it might do as the basis for a book art project along the lines of Tom Phillips’ A Humument, which had of late been very much on my mind.

Joe Mellen, Amanda Feilding, and Rock Basil Hugo Feilding Mellen

Joe Mellen, Amanda Feilding, and Rock Basil Hugo Feilding Mellen

Written by Joseph Mellen, and dedicated to ‘Amanda,’ The Secret Sonnets (Glucocracy, 1976) comprise forty sonnets that, at first glance, appear to be proper love poems, mostly traditional, if somewhat on the cosmic side. They are lovely to read, wistful and optimistic lines of absence and yearning. But strange terminology crops up with nagging frequency among the Homeric and Arthurian allusions: brainblood volume, cerebrospinal fluid, constricted veins, vitamin C sugar rule, sugarlack. Curiosity prompted me to take a closer look and I was surprised to discover that Mellen has a website on which in short order he presents the bare facts:

Born 1939. Turned on to pot 1963, mescalin 1964. 1965 met Bart Huges in Ibiza, took first acid with him and helped him with the English version of his scrolls, “Homo Sapiens Correctus” and “The Ego”. In these works he described his discoveries of the two mechanisms of blood flow inside the brain. The first explains how expanded consciousness is caused by an increase in the capillary volume of the brain and the second how the speech system controls the distribution of blood to the centres in action by repressing function in other parts.

Bart’s vision was from an evolutionary standpoint. What he saw which had never been seen before was the effect of adopting the upright position on the volume of blood in the brain and the significance of the sealing of the skull at the end of growth. The loss of a mouthful of blood from the brain at this time explains why man has always sought the means of restoring the lost paradise of childhood by various methods such as standing on the head, including taking drugs.

The realization that the sealing of the skull had the effect of suppressing the pulsation in the brain arteries, that is the expansion of the arteries on the heartbeat, led Bart to conclude that the opening of a hole in the skull would restore the expansibility of the brain membranes and allow this pulsation to reappear, bringing with it the spontaneity and playfulness of youth that was lost with the onset of adulthood. In 1965 he trepanned himself. In 1970 I followed his example. With my partner Amanda Feilding, who stood for parliament on the ticket “Trepanation for the National Health”, I later campaigned to have the operation made available for those who want to regain the brain metabolism of childhood.

Huges, who Mellen called ‘my teacher, or guru if you like,’ was perhaps the first contemporary person to practice self-trepanation. Mellon was the second:

after a few bosh shots, which are described in my book Bore Hole, I trepanned myself. Originally I used a hand trepan, something like a corkscrew but with a ring of teeth at the bottom of the shaft. It was an awkward procedure, a bit like trying to uncork a bottle from inside it, and it was unsuccessful. Subsequently I used an electric drill, which was much easier. It was comparatively simple.

I was alone in the flat – Amanda was in New York – so when it was done I busied myself with clearing up the room and then waited to see if anything happened. In the next three or four hours the feeling I had was one of increasing lightness, literally as if a weight was being lifted from my mind. I began to notice it probably an hour after I’d finished the operation, and then it grew stronger. I hadn’t really known what to expect and it was rather exhilarating feeling this gradual lightening. Would it last? Well, it remained with me till I went to sleep, and the next morning I was amazed to find that the feeling of lightness was still there. I hadn’t come down. And in the days that followed I realized that it was a permanent change in my consciousness that had taken place. I was in a better place, ready for anything.

I always found the worst part of the coming down from a trip was the last part, when the heaviness of the old familiar adult routine set in again. After trepanation that is the part that you don’t have – you stay just above that. I have to say that it is well worth it.

* * *

The high from a hole in the head is no more than a gentle lift. If you call an acid high 100 and, say, a good hash 60, then the hole would be no more than 30. What it does, however, that is extremely valuable, is relieve the Ego from the need for chronic repression. The speech system can float again, as in childhood.

Shortly, thereafter, Mellen filmed Feilding, performing the same procedure. The film Heartbeat in the Brain, has rarely been shown and has never been officially released, although alarming stills and snippets circulate on the web and a few choice moments are included in the 1998 documentary film A Hole in the Head.

Amanda Feilding, still from Heartbeat in the Brain (1970)

Amanda Feilding, still from Heartbeat in the Brain (1970)

Feilding and Birdy

Feilding and Birdy

Mellen and Feilding opened the Pigeonhole Gallery on Langton Street in Chelsea and in 1975 Mellen self-published through his imprint Glucocracy an account of his experiences entitled Bore Hole, which contains one of the most unforgettable first lines in the history of the printed word:

This is the story of how I came to drill a hole in my skull to get permanently high.

I was fortunate to catch up with Joe Mellen who was willing to submit to an interview. It turns out that the world is also apparently catching up with Joe Mellen. After 40 years Bore Hole is being properly published and Mellen will be lecturing in July.

vf: It goes without saying that much of your notoriety is surrounding your advocacy of trepanation, and your relationship with the two other advocates and fellow self-trepanation pioneers Bart Huges (of whom you have said you were a disciple) and Amanda Feilding; the fact that you wrote a book, Bore Hole, in 1975 about your experience; and that you filmed Feilding performing her own trepanation in 1970, which became the legendary ‘lost’ film Heartbeat in the Brain. In a world where everything seems immediately available, and no book or record album is so obscure that it cannot be located online in two minutes, this film seems almost not to exist at all, although of course I have seen stills and a few snippets. Will it ever enjoy a proper release and it is ever possible to see it (I read that it was last screened in 2011)?

The film certainly does exist – the original, which was on Super 8, Amanda still has. The quality of the film was exceptional – so good that when we put on an exhibition of blown-up stills from it at PS1 in New York (I guess it must have been in the seventies, though I can’t remember for sure), the exhibition was called “Trepanation for the National Health”, the blow-ups were as large as 30” by 40” and they were still of good definition, if a bit grainy, and the colour was excellent. I’m afraid I can’t say if and/or when Amanda might show it again. I know that she once gave a film maker called Eli Kabillio permission to include an excerpt for his film A Hole in the Head on condition that he wouldn’t let it be reproduced, and, needless to say, he did. The exhibition in New York was amazing I must say. It was in a large room, 30 x 40 feet, and the blow-ups were arranged in three tiers all around the walls – it was extraordinary, something Egyptian in scale, and there were pieces of text cut in amongst the pictures explaining what was happening and why.

vf: It must be gratifying that Bore Hole is receiving proper respect by being republished later this year by Strange Attractor Press and you that will be speaking on Bart Huges at the third Breaking Convention in July. How did these two events come about for you?

I went to an event at the October Gallery a few months ago – they hold psychedelic evenings once a month – and my friend Dave Luke asked me if I could get him a copy of Bore Hole. I said I couldn’t, that I tried many times to get it published without success and he said I know someone who’ll publish it. I should say that Dave is central to all the psychedelic events that take place. He is energetic and sympathetic, just a great guy.

Here are the emails relating to this, which I like very much. First Dave’s to Mark Pilkington, the publisher, and then his reply:

Hi Mark,

I had the pleasure of meeting up with Joey Mellen (cc-ed in) the other night and he was discussing his classic book Bore Hole which is now out of print (I know because I tried to get a copy recently). I suggested it would be ideal for a print on demand type of distribution. Is this anything that Strange Attractor would be interested in?

All the beast,

Dave

* * *

Hi Dave! Hi Joey!

Cosmic coincidence control must be in full effect – I was quite really just thinking how great it would be to reissue Bore Hole.

I’m actually in Los Angeles until the weekend – dahhling – but Joey it would be great to discuss this with you, and I have no doubt we could do a fantastic edition, ideally with some extra material.

Transatlantic greetings to you both

Mark

You can imagine how wonderful that was for me – for forty five years I’ve been trying and suddenly, whoof, just like that!

At the same event that night I said to Dave that it was time I gave a talk about Bart and he put me in touch with the organisers of Breaking Convention. As Elvis would say, “Oh such a night!”

vf: What is/was Glucocracy?

Glucocracy was the name Amanda and I gave to our business, which was colouring antique prints and trying to sell them. We had a card printed with GLUCOCRACY in the middle and under it was printed “non-mistake making organization”. On our first attempt to sell some we went to the Army and Navy Department Store in Victoria, because it was the first name that appeared in the Yellow Pages under Department Stores. We asked someone for the picture department and they said third floor. On leaving the lift we met a lady and asked her for the picture buyer. It’s me, said Mrs Grant. She bought 26 of our prints for £3 each. I gave her our business card. She looked at and said “that’s rather a sweeping statement isn’t it?” Well I said you wouldn’t want us to make any mistakes in our colouring would you? Phew!

vf: Why did you select the word and what is its significance?

Glucocracy was a word I coined. You can surmise that I had a classical education. I thought “rule by sugar” had a comical aspect, but also described exactly what was required in expanded consciousness.

vf: Did it produce titles in addition to Bore Hole and The Secret Sonnets?

No. Both of these were published by me in editions of 500. The sonnets were spotted by a lady who wrote about shopping in The Times. She printed one just before Valentine’s Day, offering the little book for sale for £1. We sold 500. I still have a few copies from the overrun.

vf: The postscript of The Secret Sonnets reads: There is a secret message in these sonnets | the key to the code will be printed | when the illuminated version is published. Can you tell me a little bit about the illuminated version?

It remains to be seen! The original idea was that Amanda would illustrate it one day, but that day never arrived. But who knows … ?

vf: Is it in progress? Will it be published by Strange Attractor?

Who knows?

vf: Can you give us a hint about the secret?

It was a statement of the basic facts about the mechanism of brainbloodvolume. I wrote it out and then divided it into 40 short bits of two or three words each and then wrote each sonnet around those words. I can’t remember now what the statement was, but I’ve still got a record of it somewhere.

vf: Does the Pigeonhole Gallery still exist?

No, sadly not. It was opened by Amanda and me in 1974. We had a pigeon that lived with us – we had found it as a baby when its mother died and it grew up fixated on Amanda – so the name Pigeonhole combined Birdy with the hole in the head.

vf: I understand that you read classics at Oxford. Is that an upside down copy of Kierkegaard (half blue/half black, divided by a white stripe) on the bookshelf behind you in your photo?

My classical education was at prep school and Eton, not Oxford, where I read law. I learnt Greek and Latin from age eight. The book in question is actually The Brothers Karamazov. My favourite novel, by far, is Wuthering Heights. I read Freud deeply, 14 books, studied on acid – he is a real hero – I consider The Interpretation of Dreams the greatest book of the 20th century. I also like Nietzsche very much – particularly The Genealogy of Morals …. nowadays I read mainly factual books, especially in the field of evolutionary biology … in literature I stick mainly to the classics, since there are so many great books that have stood the test of time, all the obvious ones, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky etc – I’ve read the complete works of Shakespeare, naturally …

* * *

Joe Mellen is alive and well! On Sunday, July 12, he will present his paper Introducing Bart at Breaking Convention 2015, The 3rd International Conference on Psychedelic Consciousness at University of Greenwich, Old Royal Naval College, London, July 10-12, 2015. Amanda Feilding, who ran for British Parliament twice on the platform Trepanation for the National Health, is founder and director of the Beckley Foundation for Consciousness and Drug Policy Research. Bart Huges died in 2004.

Further reading:

Bart Huges Questioned by Joe Mellen, The Transatlantic Review, No. 23 (Winter 1966-7), pp. 31-39

Eccentric Lives and Peculiar Notions (Chapter 12, The People with Holes in their Heads), 1999, John F. Michell

Like A Hole in the Head, Cabinet Magazine, Issue 28 Bones Winter 2007/08, Christopher Turner

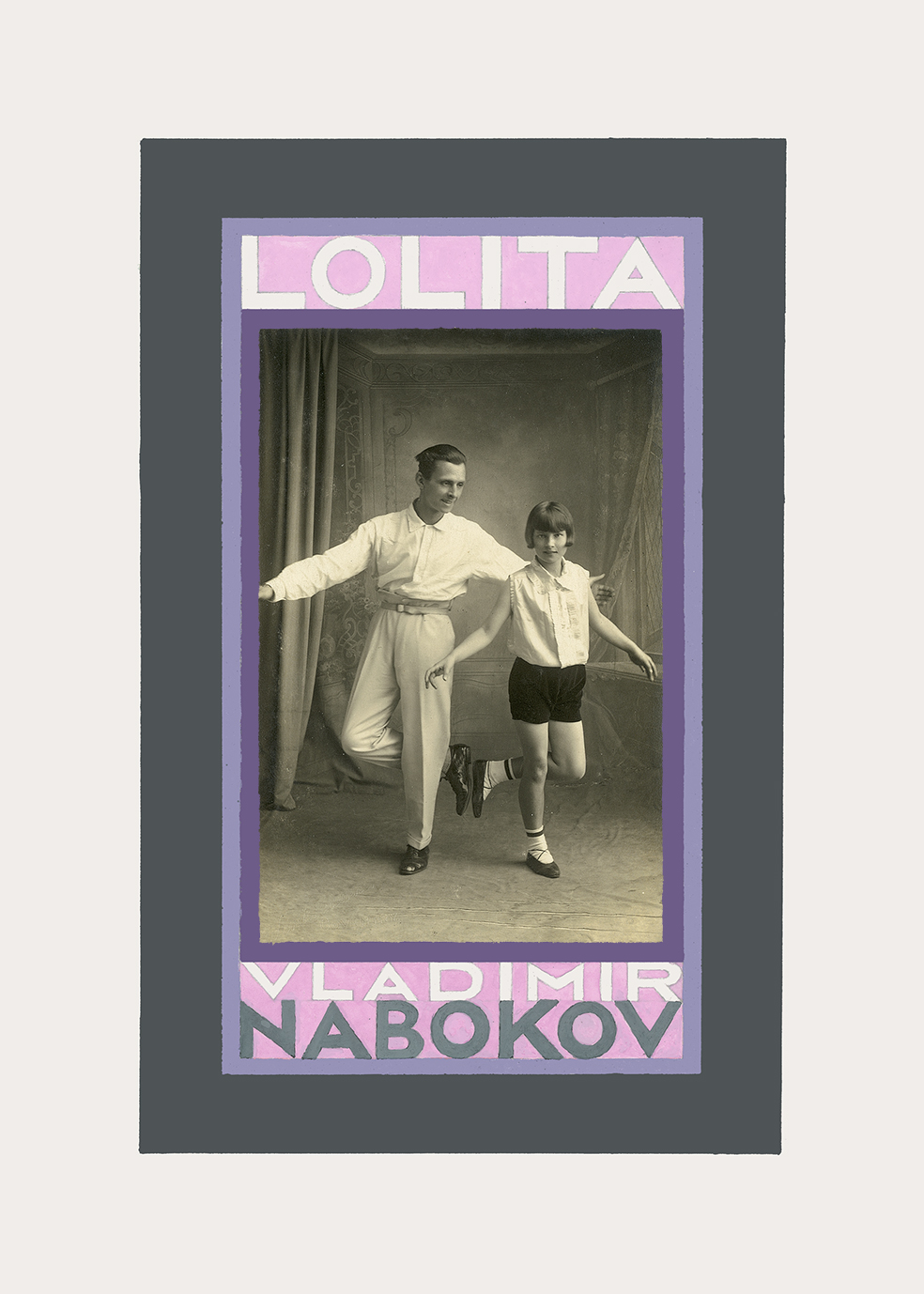

Joe Mellen

Joe Mellen