lolita, tom phillips

In 1994, during my final weeks at the Yale School of Architecture, I attended a lecture at the Yale Center for British Art, the repository for some of philanthropist’s Paul Mellon’s vast art collection and a building which was, incidentally, architect Louis I. Kahn’s last major work. Kahn was an architect with close ties to Yale (where he taught in the ‘40s and ‘50s and where his first significant commission, the Yale University Art Gallery, was completed in 1953) and his work interests me professionally, but my interest in Mellon is more personal: we each attended not only Yale, but also tiny St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland (although Mellon attended St. John’s only briefly in 1940 before joining the OSS). Among innumerable philanthropic endeavors Mellon is well known for commissioning or endowing important works of architecture, notably I.M. Pei’s West Wing at the National Gallery of Art and Eero Saarinen’s Morse and Stiles Colleges at Yale, as well as Richard Neutra’s and Robert Alexander’s Mellon Hall at St. John’s. Significantly, Mellon was also the financial support behind the Bollingen Press, founded by his wife Mary Conover Mellon and discussed elsewhere in this blog.

The artist Tom Phillips was the person I went to hear that evening. He was speaking at the opening reception for a retrospective exhibition of his work originally organized by the Royal Academy of Arts. Painter, poet, composer, creator of series, illuminator, maker of books, illustrator and gloss of Dante’s Inferno, postcard collector, recovering stencil addict, and discoverer of the secret and the magical and the enduring amongst the most quotidian and ephemeral, one of Phillips’ most engaging practices is that of isolating fragments of text or images from artworks, postcards, books and from them creating startlingly original, expressive, and intellectual work. I was introduced to Phillips’ work while an undergraduate at St. Johns where I discovered his Inferno and soon thereafter his ‘treated’ novel A Humument. The latter (an ongoing work begun 47 years ago and enjoying its fifth incarnation, or six if you count the iPhone/iPad app) is only the most well-known, but there are many examples of this mode of creation, most poignantly (for me) the series After Ter Borch in which he painted what by any standards is a rather uneventful section of the Dutch artist’s painting The Concert and elevated it to a powerful abstraction; and another series,The Flower Before the Bench, which could be viewed as a sort of reductio ad absurdum of his work Benches, but what is in reality a form of transubstantiation in which representation is miraculously abstracted into pure color and form and then back again into representation.

Tom Phillips has designed book covers and his work has also appeared on album covers, notably King Crimson’s Starless and Bible Black (a cover I cannot see without hearing Richard Burton intoning the opening lines to Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood) and Brian Eno’s Another Green World (a detail from After Raphael). Eno’s own processes owe a great debt to Phillip’s, and no wonder: Eno was Phillips’ ‘best student’ and Phillips obviously taught him well. To listen to Tom Phillips discuss his daily use of A Humument as an oracle along the lines of the I Ching, and to read his A Postcard Vision, is to experience the uncanny source of Eno’s various predilections and processes, not to mention his Oblique Strategies cards.

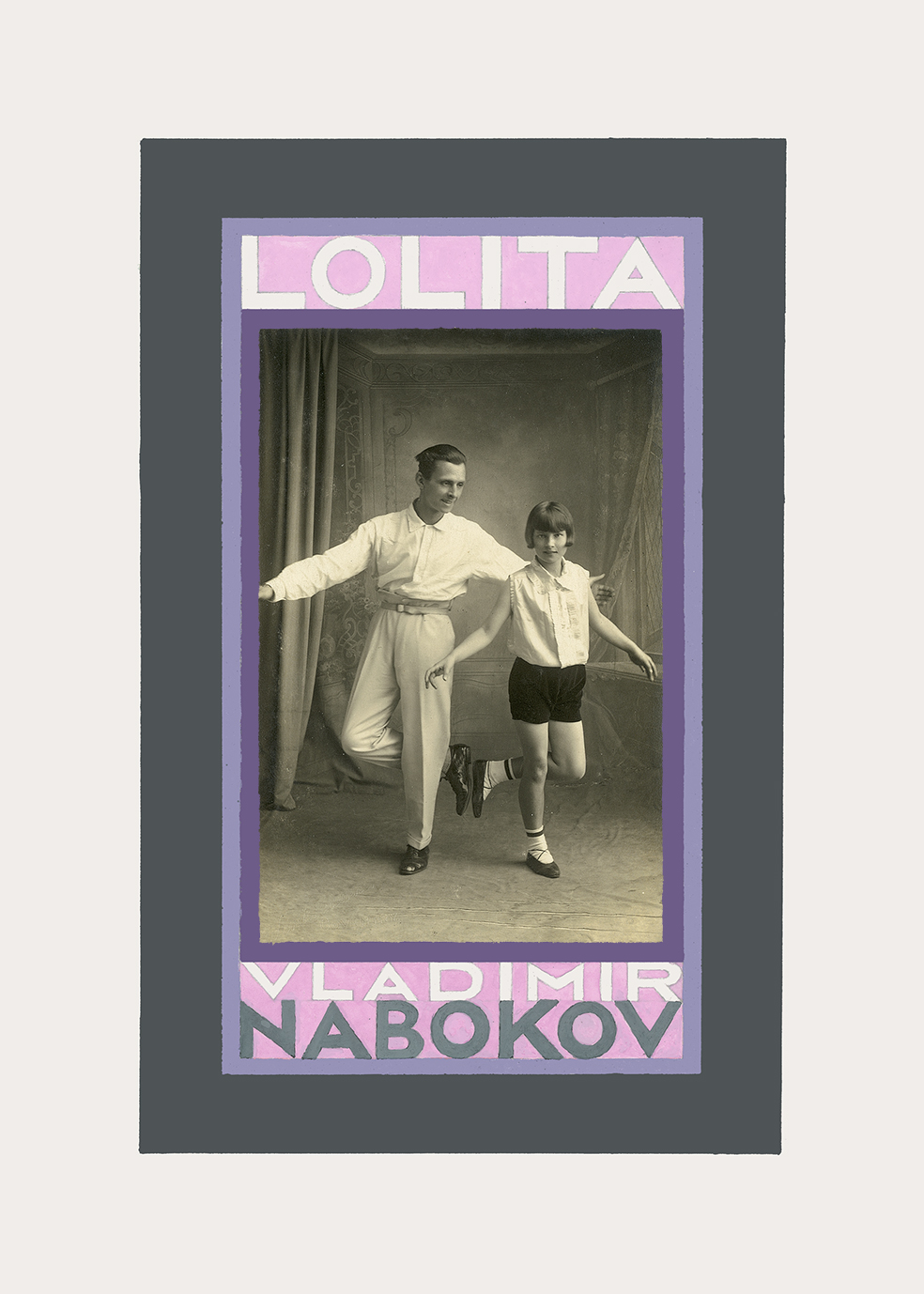

Two years ago, while working on Lolita – The Story of a Cover Girl: Vladimir Nabokov’s Novel in Art and Design(co-edited with Yuri Leving), I approached Phillips about providing a conceptual cover for the book’s gallery. Let it simply be said that I missed the opportunity to include it in the book, but for his part Phillips actually did create a cover, and now this cover is available as a large limited edition print.

Tom Phillips was kind enough to submit to an interview, and I am delighted to include it here:

JB: First of all, presumably the image on your wonderful Lolita cover is a postcard from your collection. What is its provenance and where did you acquire it?

TP: You’re right, I have a huge collection of photographic postcards from before World War II. I am currently publishing some of them in a series of books for the Bodleian Library under various headings (Bicycles, Hats, Walls, Weddings etc). When you mentioned Lolita I went to the file of ‘Girls’ but not one of the five hundred or so really spoke her name. I was stuck. Then I tried other headings and there she was under ‘Dance’ and Humbert Humbert with her. Unlike the film Lolita she is the right sort of age, or slightly under, perhaps eleven rather than twelve. But I love the dance itself which has both a touch of lepidoptery and a charged proximity/separateness of the dancers. All no doubt innocent enough in that distant period, yet answering the question ’Lolita?’ emphatically for me. There was no point in looking for another image. Sultry colours in the slightly Russian border finished the job. She is creeping out of the chrysalis and he is tiptoeing into the trap. What I like about the privately produced cards I collect is their implications of possible narrative. Here Nabokov’s book takes up one such story.

JB: I was disappointed to learn that your series of treated books Humbert’s Obliterated Rhymes has nothing to do with Lolita’s narrator, but no matter! You’ve been quoted as saying “My work is a kind of game. A serious game.” This is something that Nabokov might have said (or perhaps Samuel Beckett, although it was M.C. Escher who actually did say something very similar). Do you feel an affinity with Nabokov on any level? Do you enjoy any of his books?

TP: The Obliterated Rhymes stalks another Humbert, Humbert Wolfe, a minor poet but popular in his day. I kept on seeing his ‘Cursory Rhymes’ in secondhand bookshops and it was the connection with Nabokov that finally drew me to it, as well as its spacious pages. I’ve made or partly made ten or so versions of the book. My favourite Nabokov novel is Pale Fire. No surprise there. But Lolita ranks second for me and another ideal read for the game player.

JB: Earlier I mentioned After Ter Borch and The Flower Before the Bench. It’s difficult to express what is so compelling about these, and so many others of your works, but I can imagine your boundless curiosity, your habit of looking deeply and closely, and your interest in the processes of creation and disintegration, not to mention processes of mechanical and photographic reproduction. And so I want to ask you in a very clumsy way: alchemist that you are, what is it that you are revealing from behind or within what might otherwise be termed ‘banality?’

TP: I was very touched that you mentioned the Ter Borch variations, which no one has ever remarked on before and which are favourites of mine. Like the postcards they are part of an acceptance world. Each different reproduction of ‘The Concert’ is in it’s own key of colour and has its own vibrato and each is individually poignant. Each for its observer was also a truth. And the same with postcards. These views of bits of the world have the guarantee that they were accepted as depictions of the real, not fictions and to their original observer/purchaser not at all banal. More likely the ideal.

JB: How about an Eno tidbit?

TP: You mentioned that I taught Brian. Others did too, but music made for a specially strong bond. However I remember that on the first day in the first class he announced his inventive mind. The class was doing a life drawing which I’d told them to make only using dots. The noise was fun in itself but I recall that, once we stopped, he tore off all the bits of his paper that didn’t carry the image, thus making the figure twice, a two dimensional sculpture, and this in deeply provincial Ipswich in his home county in his first hour of art school. Brave and bold as he still is, now not my student of course but a friend of forty years standing.

JB: Finally, the floor is all yours: is there anything else you would like to say?

TP: This seems a good opportunity for promotional adverts; so here they come. I’ve enjoyed using new technologies since co-directing my version of Infero with Peter Greenaway. The whole idea of a website instead of lots of catalogues is wonderful. I take pleasure in maintaining it and in keeping up a personal blog. I love my iPad and have produced an app for it which contains the whole of A Humument looking like church windows, each page truly part of an illuminated book. My latest venture in medieval modernity is to make a USB of Humument pages with myself reading the text. Recently I’ve started with Twitter. I like its constraints and add one of my own to make it more interesting. All my tweets are in rhyming pentameters. Not poetry exactly, but fun to do; and another vanity.

My sincerest thanks to Tom Phillips and Lucy Shortis!