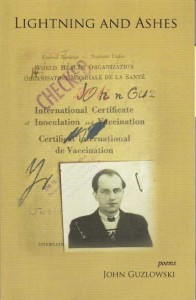

lightning and ashes, john guzlowski

In researching Tadeusz Borowski, I encountered this slim volume of remarkable poems by John Guzlowski based upon his parents’ experiences as slave laborers in the Nazi death camps during WWII. Like the writings of Borowski, these poems are understated, clear, unflinching and, ultimately, utterly heartbreaking in their depiction of the intense cruelty and immense suffering that ordinary people (in this case Tekla Hanczarek and Jan Guzlowski) endured. Guzlowski, who was himself born in a displaced persons camp in Germany in 1948, and emigrated to America with his parents in 1951, is a retired literature and poetry teacher and a seemingly tireless blogger. Of his numerous blogs I recommend Lighting and Ashes , Writing the Polish Diaspora and Writing the Holocaust.

In researching Tadeusz Borowski, I encountered this slim volume of remarkable poems by John Guzlowski based upon his parents’ experiences as slave laborers in the Nazi death camps during WWII. Like the writings of Borowski, these poems are understated, clear, unflinching and, ultimately, utterly heartbreaking in their depiction of the intense cruelty and immense suffering that ordinary people (in this case Tekla Hanczarek and Jan Guzlowski) endured. Guzlowski, who was himself born in a displaced persons camp in Germany in 1948, and emigrated to America with his parents in 1951, is a retired literature and poetry teacher and a seemingly tireless blogger. Of his numerous blogs I recommend Lighting and Ashes , Writing the Polish Diaspora and Writing the Holocaust.

“In terms of my treatment of their lives, I’ve tried to use language free of emotions. When my parents told me many of the stories that became my poems, they spoke in plain, straightforward language. They didn’t try to emphasize the emotional aspect of their experience; rather, they told their stories in a matter-of-fact way. This happened, they’d say, and then this happened: The soldier kicked her, and then he shot her, and we moved on to the next room. I’ve also tried to make the poems story-like, strong in narrative drive to convey the way they were first told to me.”

“After my dad died, my mom started talking about her experiences in the war. She had never done that before except in the most general terms. I remember her saying how hard the war was. When I was a kid and would ask her about the war, she would say, “If they beat you, you run. If they give you bread, you eat it.” And then she’d wave me away, tell me to do something, leave her alone. I wrote about this in my poem “Here’s What My Mother Won’t Talk About.”

Just a girl of nineteen

with the grace of flowers

in her hair

coming home

from the pastures

beyond the woods

where the cows drift

slowly, through a twilight

of dust, warm and still

as August

She finds her mother

a bullet in her throat

her sister’s severed breasts

in the dust by her feet

the dead baby

still in its blanket

It all ends there

not in the camps

but there

Ask her

She’ll wave her hand

tell you you’re a fool

tell you

if they give you bread

eat it

if they beat you

run